|

(L to R): Sparrow Field at Cochran Shoals CRNRA, by Gabe Andrle. Cochran Shoals CRNRA, by Adam Betuel. LeConte's Sparrow, by Adam Betuel. by Dottie Head, Director of Communications

Birds Georgia was recently awarded a Bill Terrell Avian Conservation Grant from the Georgia Ornithological Society (GOS) for a habitat restoration project that will restore riparian meadows and wildlife corridors along the Chattahoochee River. The restoration project will focus on restoring early successional habitat at the Cochran Shoals Unit of the Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area (CRNRA). “We’re excited to receive this generous grant from GOS to restore bird-friendly habitat at Cochran Shoals CRNRA,” says Adam Betuel, director of conservation for Birds Georgia. “The Cochran Shoals Unit is a popular birding spot because it includes a mix of microhabitats, including riparian meadow, riparian woodland, and beaver-maintained wetland, making it possible to see a wide array of birds throughout the year, but particularly during spring and fall migratory periods.” Part of the project will focus on restoring the “sparrow field,” a roughly seven-acre portion of the area that is known to host an array of sparrows, including notable species such as Grasshopper Sparrow, Henslow’s Sparrow, Clay-colored Sparrow, and LeConte’s Sparrow, among the more regular suite of species like Song Sparrows and Chipping Sparrows. Henslow’s and Grasshopper Sparrow are both listed as High Priority Species on Georgia’s State Wildlife Action Plan. “As part of the grant-funded work, Birds Georgia will not only restore some of the sparrow field, but also improve its ecological value by removing non-native species and introducing a greater diversity of native plants that would help beneficial pollinating insects including species like the endangered monarch butterfly,” says Adam Betuel, director of conservation for Birds Georgia. In recent decades, many birds that rely on open and early-successional habitats have seen a decline in population due to habitat loss, pesticide use, and a variety of other factors. Grassland birds in particular have seen a decrease in population by about 53% since 1970 according to a 2019 study (https://www.3billionbirds.org/findings) conducted by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, National Audubon Society, and other partners. In collaboration with the National Parks Service at CRNRA and the Chattahoochee National Park Conservancy, Birds Georgia will improve and restore a minimum of 16.5 acres of bird-friendly habitat at the Cochran Shoals Unit of CRNRA, including the “sparrow field.” The remaining acreage will be treated for invasive plant species and opened up where possible to support early successional habitat acting as a buffer to protect the meadow space from problematic plant species. Birds Georgia’s Habitat Team and volunteers will remove non-native invasive plant species and knock back undesirable woody species, install new native vegetation, and promote the spread of currently existing native vegetation. In the future, Birds Georgia will be seeking grant funding to create a wildlife corridor connecting the historic “sparrow field” to a site that is being opened up and restored into more grassland habitat for the introduction of a federally endangered plant species. This will be done in partnership with the National Park Service, Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Georgia Power, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and other organizations. “The work that Birds Georgia will be doing at Cochran Shoals CRNRA is part of the greater Chattahoochee RiverLands effort,” says Betuel. “In partnership with the Trust for Public Land and other partners, Birds Georgia is working to improve the ecological health of the Chattahoochee River basin to restore bird-friendly habitat that will benefit birds and people, too.” Birds that will benefit from this improved habitat include Indigo Bunting, Yellow Warbler, Yellow-breasted Chat, and overwintering sparrows, as well as other resident and migratory birds who utilize riparian meadow and woodland habitat. “In addition to the on-the-ground conservation work, Birds Georgia will engage, activate, and educate the public to understand Chattahoochee watershed concerns through community conservation work days, community science initiatives, and seasonal field trips,” says Betuel. “The Cochran Shoals Unit is one of the most birded locations in metro Atlanta (as evidenced by the more than 200 bird species and more than 4,500 check lists submitted via eBird at this location) and is an ideal candidate for additional education and engagement.” About Birds Georgia: Birds Georgia is building places where birds and people thrive. We create bird-friendly communities through conservation, education, and community engagement. Founded in 1926 as the Atlanta Bird Club, the organization became a chapter of National Audubon in 1973, and continues as an independent chapter of National Audubon Society. About Georgia Ornithological Society: The Georgia Ornithological Society's (GOS) mission is to encourage the scientific study of birds by gathering and disseminating information on Georgia bird life. GOS actively promotes bird conservation by encouraging the preservation of habitats that are vital to the survival of resident and migratory birds. The GOS also gives scholarships, produces scientific publications, and provides fellowship among those interested in nature. Learn more at https://www.gos.org/home.

0 Comments

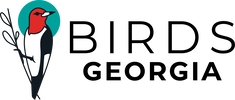

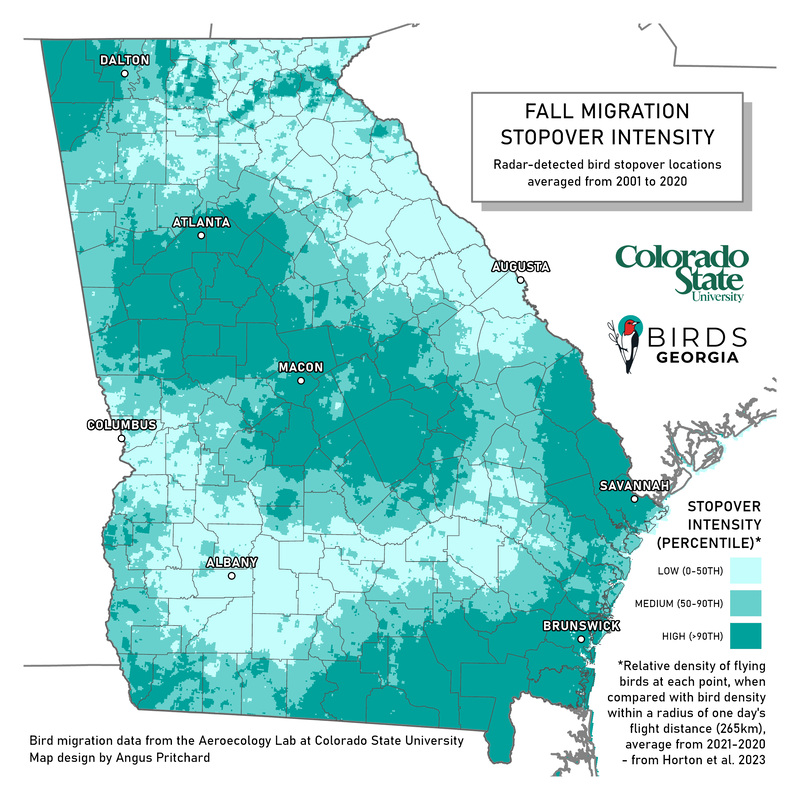

Left photo shows Fall Stopover Hotspots for Bird Migration in relation to proposed Twin Pines Mine (in yellow); Right photo shows Spring Stopover Hotspots. Via Electronic Mail

Director Jeff Cown Georgia Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division 2 Martin Luther King Jr. Drive SE Suite 1456, East Tower Atlanta, GA 30334 twinpines.comment@dnr.ga.gov Re: Comments Opposing Draft Permits for Twin Pines Mine Dear Director Cown: On behalf of Birds Georgia members across the state, we are writing today to ask you to protect the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge and the St. Marys River by denying Twin Pines Minerals’ (TPM) application to strip mine for heavy mineral sands at the doorstep of the Okefenokee Swamp. Birds Georgia’s mission is to build places where birds and people thrive. We fulfill our mission through education, conservation, and community engagement. With more than 2,500 members and more than 5,000 National Audubon Society members from across the state, Birds Georgia represents a broad constituency united by a desire to protect birds and other wildlife. Our constituents include Georgia residents, frequent visitors, and concerned citizens who understand both the significance and beauty of the Okefenokee Swamp for birds and other wildlife. At 438,000 acres, the Okefenokee Swamp is one of the most wild, pristine, and ecologically intact places in America, sheltering more than one thousand animal and plant species within its vast labyrinth of cypress forests, pine islands, and blackwater channels. In addition to providing refuge to wildlife, the Okefenokee offers an escape to hundreds of thousands of people who fish, hunt, paddle, birdwatch, and camp in its wilderness each year. As the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service put it, “The Okefenokee is like no other place on earth.” Twin Pine’s proposed strip mine endangers this world-class resource. Not only is the proposed mine dangerous in its own right, it would effectively open Trail Ridge to mining for decades to come, jeopardizing the long-term viability of the swamp. Georgia EPD, as the state agency charged with protecting and restoring Georgia’s environment, has both a statutory and moral obligation to say no. The stakes are too high, and the risks are too great. Twin Pines' proposal to mine deep into Trail Ridge adjacent to the national wildlife refuge will likely have lasting and irreversible impacts, eliminating roughly 300 acres of valuable wetlands, excavating up to 50 feet deep, withdrawing millions of gallons of groundwater, releasing air and light pollutants into the International Dark Sky Park, and discharging wastewater into the St. Marys River basin. Twin Pines has offered NO defensible assurances that; 1) their mining operations will protect the Okefenokee Swamp from permanent damage; 2) that they will protect threatened and endangered species, including Red-cockaded Woodpeckers, Wood Storks, gopher tortoises, and many other species that nest and raise young in the Okefenokee Swamp; and 3) that they will safeguard the long-term interest of the birdwatchers, kayakers, hikers, and other nature enthusiasts who visit the Okefenokee Swamp each year. The Okefenokee Swamp is a diverse ecosystem that provides critical habitat for more than 200 species of resident and migratory bird populations, as well as many other plant and animal species. Below, please find a list of the specific species that Birds Georgia is concerned will be negatively impacted by the Twin Pines Mine.

Hydrology Concerns: Birds Georgia does not believe that Twin Pines has adequately proven that the proposed mine will not harm the water levels in the Okefenokee Swamp and surrounding Trail Ridge. The proposed mining project would dig pits up to 50 feet deep into Trail Ridge, a feature integral to maintaining surface water and groundwater hydrology in the Okefenokee, St. Marys River, and surrounding areas. More than 85 scientists, including UGA hydrologist Rhett Jackson, have concluded that the mine poses a significant risk to the swamp. Even a small reduction in the amount of water in the swamp could have far reaching impacts for the wading birds and other species that live there. As indicated above, many bird species are extremely vulnerable to reduction in water levels beneath nesting trees and many more rely on the Okefenokee for feeding and shelter. Twin Pines proposed is expected to (1) lower water levels in the Okefenokee Swamp and the St. Marys River by removing more than one million gallons of groundwater per day; (2) destroy the distinct geological layers of Trail Ridge, making it difficult to reestablish wetlands and potentially reducing long-term flows to the swamp; (3) increase wildfire risk in the vicinity of the swamp by exposing peat and by increasing the duration and severity of drought in the Okefenokee Swamp and St. Marys River; (4) contaminate ground and surface water in the vicinity of the mine by liberating heavy metals, radionuclides, and other contaminants that are currently stored in Trail Ridge soils; (5) degrade habitat and harm wildlife, including endangered sturgeon and migratory birds., Question: What steps will Georgia EPD take to ensure that the water level in the swamp is not negatively impacted by the Twin Pines Mine? Stopover Habitat for Migratory Birds: Along with other partners and researchers, Birds Georgia has been working with the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Colorado State University to use radar and satellite imagery to develop BirdCast, a bird migration forecasting tool. In addition to providing multi-day forecasts of bird migration patterns over the continental U.S., BirdCast also provides real-time data on the population density and direction of migratory birds flying over the country. An analysis of BirdCast data from 2000 to 2020 revealed that the Okefenokee Swamp and surrounding environment is a critically important stopover area for vast and diverse populations of migratory birds, both during spring and fall migrations. Particularly notable, portions of Trail Ridge which include and surround the proposed mining site are hotspots for spring migration stopovers. These areas provide migratory birds with needed shelter and key food sources as they travel to and from breeding and wintering grounds. The Okefenokee Swamp could be the first landfall for many of these Neotropical migrants that just crossed the Gulf of Mexico or arrived from the Caribbean Islands. The proposed mine would disrupt these critical stopover areas in a variety of ways, by destroying vegetation and soil structure, removing groundwater, generating light and noise, exacerbating wildfires, and releasing toxic contaminants. All of these disruptions are likely to negatively impact migratory birds and their habitat in and around the mining site, as well as the broader Okefenokee ecosystem. This is especially worrisome as our long-distance migrants are the species, in general, experiencing the steepest declines and encountering the higher amount of threats. Lighting Concerns: Birds Georgia remains concerned about excess nighttime lighting associated with the Twin Pines Mine. The Okefenokee Swamp is well known for its dark nighttime skies, and nearby Stephen C. Foster State Park is designated as a Dark Sky Park. Migrating birds are extremely sensitive to nighttime lighting which can act as a magnet pulling them off course and into brightly lit areas where they face threats ranging from building collisions to predation. Question: How will the Georgia Environmental Protection Division ensure that birds are not negatively impacted by nighttime lighting from the Twin Pines Mine? Birding and Outdoor Recreation: In addition to the many bird and animal species that rely on this diverse ecosystem, the Okefenokee Swamp is a popular tourist destination. Each year, more than 650,000 people visit the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge to watch birds, camp, canoe, kayak, hike, and enjoy this unique natural area, generating roughly $88 million in economic impact in Charlton, Clinch, and Ware counties. In fact, the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) provides more economic benefit to Georgia and Florida than any other NWR. Question: How will the Georgia Environmental Protection Division ensure that Twin Pines does not cause irreparable harm to this ecosystem and negatively impact recreational opportunities and tourism-related economic benefits from Okefenokee Swamp-related tourism? Overwhelming Opposition to Mine: Finally, no permit application in Georgia history has drawn as much opposition as this one. Since Twin Pines proposed mining Trail Ridge in 2018, public opposition has been overwhelming and unwavering, with more than 200,000 individual comments at the state and federal level as of April 1, 2024. Birds Georgia submitted comments during the March 5 Public Meeting and listened to the 3+ hours of testimony. Not a single person spoke in favor of the mine. In addition, people from across Georgia have written letters and called their legislators in unprecedented numbers, and at least nineteen local governments have passed resolutions calling for the protection of the Okefenokee Swamp. It is clear that Georgians DO NOT WANT the Twin Pines Mine near the Okefenokee Swamp. In closing, Birds Georgia feels strongly that the Okefenokee Swamp is a unique ecosystem that should be protected from activities that could disrupt bird life. We continue to encourage the Georgia EPD to deny these permits for surface mining along the Okefenokee Trail Ridge. Thank you for your consideration. Sincerely, Jared Teutsch Executive Director  Birds Georgia will host the inaugural Georgia Bird Fest Summit on Saturday, April 20, from 8:30 to 2:00 PM, at the Classic Center, in Athens, GA. J. Drew Lanham, Ph.D., poet laureate, MacArthur fellow, and distinguished professor of wildlife ecology at Clemson University will give the keynote address on Coloring the Conservation Conversation. The Georgia Bird Fest Summit will bring bird enthusiasts from across the state to share knowledge and inspiration about birds, birding, and related issues in Georgia. The Georgia Bird Fest Summit is part of the ninth annual Georgia Bird Fest which returns this spring with more than 40 events between April 6 and May 4. Participation in the Georgia Bird Fest Summit and Georgia Bird Fest events provides critical support for Birds Georgia’s conservation, education, and community engagement programs. The event will officially begin at 8:30 AM on Saturday, April 20, with the keynote address, entitled, Coloring the Conservation Conversation, by J. Drew Lanham. He will discuss what it means to embrace the full breadth of his African-American heritage and his deep kinship to nature and adoration of birds. The convergence of ornithologist, college professor, poet, author and conservation activist blend to bring our awareness of the natural world and our moral responsibility for it forward in new ways. Candid by nature — and because of it — Lanham will examine how conservation must be a rigorous science and evocative art, inviting diversity and race to play active roles in celebrating our natural world. Avid Bookshop, an Athens-area book store, will be on hand selling a selection of Lanham’s books that will be available for the books signing event. Drew Lanham, Ph.D., is a certified wildlife biologist, an academic, writer, artist, and public intellectual, from Edgefield and Aiken, South Carolina. He is an Alumni Distinguished Professor, Provost's Professor and Master Teacher of Wildlife Ecology at Clemson University, where his most recent scholarly efforts address the confluences of race, place and nature. A 2022 MacArthur Fellow, Dr. Lanham was also named one of the 100 most influential Black Americans by "The Root", in 2022. Creatively, Drew is the Poet Laureate of Edgefield County, South Carolina and the author of Sparrow Envy - Poems, Sparrow Envy - A Field Guide to Birds and Lesser Beasts, and The Home Place - Memoirs of a Colored Man's Love Affair with Nature. In addition, the Summit will feature six breakout sessions from which attendees can choose. To see the full schedule of events, please visit our website. Early bird registration (through April 5) is $100 ($50 for students with a .edu email address). After April 6, the registration fee increases to $125 ($62 for students). Refreshments and lunch are included in the Summit registration fee. Registration is now open for the Georgia Bird Fest Summit and other Georgia Bird Fest on our website. Birds Georgia would like to thank the following event sponsors: Georgia Power Company, Barefoot Garden Design, Bird Collective, BirdNote, Bonsai Leadership Group, eBird, Jekyll Island Authority, Lynx Nature Books, Patagonia, Sticker Mule, Southwire, and Vortex. Thanks to a generous grant from the Disney Conservation Fund, Birds Georgia has been working with Dr. Kyle Horton at Colorado State University (CSU) to measure migratory bird activity over the state during spring and fall migration. These maps were the result of that work. Each fall and spring, billions of migratory birds travel across North America making their way between breeding grounds and wintering grounds. These birds must constantly confront changes to the landscapes below caused by natural and man-made forces, including the rapid proliferation of brightly lit nighttime landscapes. While migration takes part in the skies, birds must stop along the way to rest and refuel. Birds Georgia wants to know WHERE these birds are stopping and to gain a better understanding of WHY they choose these locations. By pairing migration intensity measurements from nearby weather stations with other environmental variables, the CSU team was able to train a machine learning model that predicted migration intensity in Georgia during spring and fall from 2000 to 2020. With these predictions, they were able to establish regions considered hotspots of bird migration stopover and refueling. The darker areas on the maps represent higher concentrations of birds stopping over to rest and feed. In over 70% of the models that were created, skyglow (or night time lighting) was identified as a highly influential and consistently positive predictor of bird migration stopover density across Georgia and the United States. The findings of this study point to the ever-expanding threat that brightly lit night skies pose to birds, particularly during migration. In short, migratory birds are extremely sensitive to nighttime lighting which acts like a magnet pulling them into brightly lit areas and cities where they face threats ranging from building collisions to predation. In recent years, the Colorado State Team has been working with state organizations, like Birds Georgia, to provide state-level migration forecasts enabling us to issue Lights Out alerts on nights of peak migratory bird activity. Learn more about this project or view the nightly forecast for Georgia enabled by this technology on our website. by Dottie Head, Director of Communications

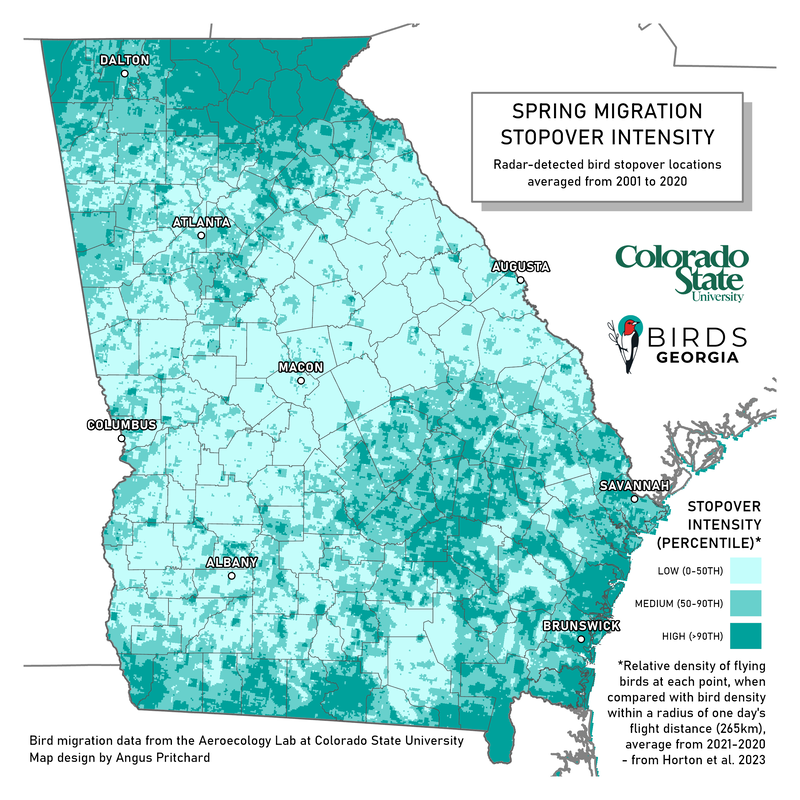

This spring, Birds Georgia will kick off the ninth year of Project Safe Flight Georgia, a project to study bird-building collisions across the state. Since the program began in 2015, volunteers have collected data from more than 4,200 birds representing 135 different species that perished after colliding with buildings. Recently, Project Safe Flight was extended to coastal Georgia with volunteers patrolling routes in Savannah and Brunswick as well as continuing routes in metro Atlanta. Ruby-throated Hummingbirds continue to be the most commonly found species, followed by Tennessee Warbler, Swainson’s Thrush, Cedar Waxwing, and Ovenbird. Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, Wood Thrush, American Robin, Common Yellowthroat, and Red-eyed Vireo round out the 10 most commonly collected species by Project Safe Flight volunteers. Current research estimates that between 350 million and 1 billion birds perish each year from colliding with buildings in the U.S. Attracted by nighttime lights and confused by daytime reflections of habitat in shiny windows, many birds become disoriented and fly into the buildings, ending their journeys and their lives prematurely. “Birds Georgia launched Project Safe Flight in 2015 to gain a better understanding of the bird-building collision problem across Georgia,” says Adam Betuel, Birds Georgia’s director of conservation. “We have been studying what species are most likely to collide with buildings, how many birds are affected, and what parts of the state are most problematic. Since the program began, we’ve learned a lot about how and where building collisions are occurring, and we’ve implemented some programs and changes to help reduce collisions and make Georgia safer for migrating birds.” Monitored sites included public sidewalks, private businesses, university campuses, and a handful of government buildings. Each spring and fall, Project Safe Flight Georgia volunteers patrol predetermined routes across the state collecting birds that have collided with buildings. Patrols run from late March through May each spring and again from mid-August to mid-November in the late summer and fall, covering peak migration months for many species. There are several ways the public can help. One of the easiest is to reduce nighttime lighting during peak migration periods. The Lights Out Georgia program was designed to encourage homeowners and commercial properties to turn off nighttime lights from midnight to 6 AM during peak migration. New migration forecasting technology has allowed Birds Georgia to predict nights of extremely high bird migration and issues Lights Out Alerts for evenings of peak migratory activity. For more information or to sign up, please visit our Lights Out Georgia page. More information on how to make your home bird-safe, to sign up as a Project Safe Flight Volunteer, or to report dead birds you find at your home or workplace, please visit the Project Safe Flight Georgia page. Birds Georgia will host a Project Safe Flight webinar on Tuesday, April 9, at 7:00 PM to share information about bird-building collisions and causes, and to discuss ways we can make our homes and cities safer. Sarah Tolve, Bird Georgia's coastal conservation coordinator, will provide an overview of Birds Georgia's Project Safe Flight program and share how volunteers can get involved. Learn how monitoring efforts are conducted on the ground, how to report sightings, what is being done with this data, and what we’ve learned (and how the program has grown) since Project Safe Flight Launched in 2015. The program is free to attend, and sign up is now available on our upcoming events page. by Dottie Head, Director of Communications

The ninth annual Georgia Bird Fest will return this spring with more than 40 events between April 6 and May 4. Join fellow nature and bird enthusiasts for exciting field trips, workshops, and other events to celebrate and enjoy Georgia’s exciting spring migration period. This year’s event will feature the Inaugural Georgia Bird Fest Summit on Saturday, April 20, in Athens, Georgia. Dr. J. Drew Lanham, poet laureate, McArthur fellow, and distinguished professor of wildlife ecology at Clemson University will give the keynote address on Coloring the Conservation Conversation. Participation in Georgia Bird Fest provides critical support for Birds Georgia’s conservation, education, and community engagement programs. Georgia Bird Fest includes events across Georgia, from the mountains to the coast, including both in-person and virtual events and workshops. Some of the event highlights for Georgia Bird Fest 2024 include past favorites such as a tour of Zoo Atlanta’s bird collection; canoe trips on the Chattahoochee River; a Warbler Weekend in North Georgia; trips to Phinizy Swamp near Augusta and Harris Neck NWR on the coast; an overnight stay at the Len Foote Hike Inn in Dawsonville; and trips to other birding hot spots across the state. Some of this year’s virtual offerings include Birding 101, Warbler ID, Raptor ID, and a Building Your Backyard Wildlife Sanctuary webinars. This year, we’re excited to premiere a new addition to the Georgia Bird Fest lineup of events. On Saturday, April 20, Bird Georgia will host our inaugural Georgia Bird Fest Summit from 8:30 AM to 2:00 PM at the Classic Center in Athens, GA. The Georgia Bird Fest Summit is designed to bring people from the state-wide birding community together to share knowledge and inspiration about what organizations are doing in Georgia's conservation, education, and community engagement programming. The Summit will consist of our keynote presentation and six breakout sessions from which attendees can choose. Refreshments and lunch will be provided. In addition, there will be activities in and around Athens on the day of the event. We’re delighted to share that Dr. J. Drew Lanham will be giving our keynote address with a talk entitled, "Coloring the Conservation Conversation." Dr. Lanham will discuss what it means to embrace the full breadth of his African-American heritage and his deep kinship to nature and adoration of birds. The convergence of ornithologist, college professor, poet, author and conservation activist blend to bring our awareness of the natural world and our moral responsibility for it forward in new ways. Candid by nature — and because of it — Lanham will examine how conservation must be a rigorous science and evocative art, inviting diversity and race to play active roles in celebrating our natural world. Drew Lanham, Ph.D., is a certified wildlife biologist, an academic, writer, artist, and public intellectual, from Edgefield and Aiken, South Carolina. He is an Alumni Distinguished Professor, Provost's Professor and Master Teacher of Wildlife Ecology at Clemson University, where his most recent scholarly efforts address the confluences of race, place and nature. A 2022 MacArthur Fellow, Dr. Lanham was also named one of the 100 most influential Black Americans by "The Root", in 2022. Creatively, Drew is the Poet Laureate of Edgefield County, South Carolina and the author of Sparrow Envy - Poems, Sparrow Envy - A Field Guide to Birds and Lesser Beasts, and The Home Place - Memoirs of a Colored Man's Love Affair with Nature. His memoir is a past winner of the Reed Environmental Writing Award (Southern Environmental Law Center), the Southern Book Prize, and a 2017 finalist for the Burroughs Medal. It was named a memoir and scholarly book of the decade by Lithub & Chronicle of Higher Education. His forthcoming works are Joy is the Justice We Give Ourselves, The Bird I Became, and Range Maps - Birds, Blackness and Loving Nature Between the Two. Registration for Georgia Bird Fest opens on March 5 for Birds Georgia members and on March 12 for non-members. For more information or to view a full schedule of events, please visit https://www.birdsgeorgia.org/birdfest.html . Birds Georgia would like to thank the following event sponsors: Georgia Power Company, Barefoot Garden Design, Bird Collective, Bonsai Leadership Group, Jekyll Island Authority, Lynx Nature Books, Sticker Mule, Southwire, and Vortex. About Birds Georgia: Birds Georgia is building places where birds and people thrive. We create bird-friendly communities through conservation, education, and community engagement. Founded in 1926 as the Atlanta Bird Club, the organization became a chapter of National Audubon in 1973, and continues as an independent chapter of National Audubon Society today. We look forward to celebrating the 100- year anniversary of our organization in 2026. Learn more at https://www.birdsgeorgia.org/. ### A copy of this letter was sent to the Speaker of the House and all State Judiciary Committee members in the Georgia House of Representatives on February 26, 2024.

Dear Representatives, On behalf of Birds Georgia members across the state, we are writing today to express our opposition to House Bill 370. This bill is a threat to more than 50 years of salt marsh protection in Georgia and could have catastrophic impacts on our salt marsh resources and the many species of birds that rely on them. Birds Georgia’s mission is to build places where birds and people thrive. We fulfill our mission through education, conservation, and community engagement. With more than 2,500 members and more than 5,000 National Audubon Society members from across the state, Birds Georgia represents a broad constituency united by a desire to protect birds and other wildlife. Our constituents include Georgia residents, frequent visitors, and concerned citizens who understand the both the significance and beauty of Georgia’s salt marshes for birds. Please consider the following: — This bill would effectively remove the marsh as part of the public trust doctrine. The new standard would open the door for more hardening of our shorelines, which would also remove native habitat, impacting wading birds and key migratory species that rely on the marsh for nesting and resting habitat. It would also make coastal Georgia more vulnerable to storm surge and king tides. — The unique curved coastline of the Georgia Bight results in large changes of water depth between low tide and high tide every day. This intertidal zone of extensive salt marshes, expansive sand and mud flats, and undisturbed areas of beach creates huge areas of potential food resources that are exposed by the receding tide. In recognition of the value to shorebirds in the Bight, there are three Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network (WHSRN) sites encompassing much of coastal South Carolina and Georgia. The loss and/or development of Georgia’s salt marshes could threaten our state’s designation as a WHSRN. — The loss and/or development of our salt marshes in Georgia would have negative impact on the following bird species, to name a few: Saltmarsh Sparrow; Seaside Sparrow MacGillivray's subspecies, specifically); Nelson's Sparrow; Clapper Rail; Willet (the Eastern subspecies nests in Georgia’s marshlands); Marsh Wren (Worthington's subspecies, Georgia’s resident breeder); Eastern Black Rail (may already be extirpated from the state); Little Blue Heron; Tricolored Heron; Whimbrel; Roseate Spoonbill; Wood Stork; as well as other species of shorebirds that live year around or migrate through Georgia. The bottom line is what's bad for birds, is bad for people too. This bill has passed the House Judiciary Committee by a vote of 5-4. It is now sitting in Rules. We implore you to help stop the forward progress of this bill by either ensuring it does not pass out of Rules or that it gets committed to the House State Properties Committee. HB370 should not pass. It goes too far and could destroy coastal Georgia's most iconic landscape and the birds on which they depend. Thank you for your consideration. Sincerely, Jared Teutsch Executive Director Igniting Change: Birds Georgia’s Fire Training Experience with IBT at Hard Labor Creek State Park1/25/2024 By Logan Jones, Habitat Program Specialist

Birds Georgia has a new tool in their toolbox. Recently, members of the Birds Georgia conservation team—consisting of Sebastian Hagan, Sarah Tolve, and Logan Jones—underwent comprehensive fire training led by the IBT (Interagency Burn Team) at Hard Labor Creek State Park. This particular training, encompassed a pack test, online coursework, and physical training, and was designed to equip participants with an FFT2 certification (wildland firefighter type II) that aligns seamlessly with Birds Georgia’s commitment to ecological restoration. The IBT is an agreement between private, state, and federal partners that are focused on burning to help rare wildlife. Some of the IBT organizations include the Department of Natural Resources (DNR), The Orianne Society, The Longleaf Alliance, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services, Tall Timbers, The Nature Conservancy, U.S. Forest Service, and The Georgia Forestry Commission. Many of these organizations also sent staff to join in training and to lead activities such as fire shelter deployment, burn plan management, pacing and orienteering, pumps, engines, hoses, and so much more. The recent training not only strengthened staff expertise but also solidified Birds Georgia’s desire to actively engage in prescribed fires in partnership with IBT. Our goal is to align Birds Georgia’s conservation efforts with burning whenever feasible, recognizing the ecological benefits it brings to our landscapes. Prescribed fires have been proven to be instrumental in fostering early successional songbird habitat. Strategic burns create open spaces and clearings that are conducive to the growth of native vegetation, providing crucial nesting sites and foraging opportunities for early successional songbirds. These intentional fires mimic natural ignition processes, promoting biodiversity and maintaining the balance of ecosystems. Furthermore, prescribed fires help reduce the accumulation of dense vegetation, which can otherwise hinder the growth of native plants and limit the availability of suitable habitats for songbirds. By restoring a more open and diverse landscape through controlled burns, Birds Georgia is able to enhance the overall health of the ecosystem and create conditions that are particularly favorable for the flourishing of early successional bird populations. As we look ahead, Birds Georgia conservation staff are eager to employ their new certifications by contributing to prescribed burns in collaboration with the IBT. This new certification better positions our staff to support organizations across the state that conduct burns, including our partners at the DNR. In recent years, Birds Georgia has been collaborating with DNR to restore bird habitat at Panola Mountain State Park, including a restoration meadow that would benefit from a prescribed fire treatment in the coming year. Stay tuned for updates as Birds Georgia continues to work with partners to foster and improve healthy ecosystems through informed and strategic fire management practices. Together, Birds Georgia aims to kindle positive change and preserve the ecological balance of our landscapes for birds and future generations. Each spring and fall, Birds Georgia volunteers patrol Project Safe Flight Georgia routes around the state looking for birds that have been injured or killed by building collisions. This project aims to determine what species are colliding with buildings, how many birds are affected, what parts of town are problematic, and what can be done to make Georgia's cities more bird-friendly.

Since the program began in 2015, more than 2,200 birds, representing 115 different species, have been collected. This infographic shows numbers from our fall surveys. If you'd like to learn more about Project Safe Flight Georgia or to become a volunteer, visit our Project Safe Flight Georgia page. L to R, top to bottom: Beth Blalock, Michael Chriszt, Colleen McEdwards, Sally Sears Birds Georgia welcomed four new directors elected by members to the Board of Directors at their annual meeting on December 3. Beth Allgood Blalock, Michael Chriszt, Colleen McEdwards, and Sally Sears were elected for three-year terms beginning January 1, 2024. In addition, Joshua Andrews, Robert Cooper, Marc Goncher, and Susan Maclin will return to the Board of Directors for a second three-year term. Marc Goncher, Senior Legal Counsel, Environmental, Safety and Sustainability for The Coca-Cola Company, will succeed Paige Martin as Board Chair when her term ends on December 31.

Beth Allgood Blalock is an attorney with Gilbert Harrell and has a wide range of experience working on land-based environmental issues. Her primary practice areas include environmental regulatory, compliance, and permitting issues, and the acquisition and redevelopment of properties with environmental impacts. She serves as a lecturer on brownfields and regulatory issues in Georgia, sits on the board of the Georgia Brownfield Association and the Georgia Environmental Conference Steering Committee and is currently an adjunct professor at the Georgia State University College of Law. Beth is the lead facilitator of the Institute for Georgia Environmental Leadership (IGEL) and a 2016 IGEL graduate. She and her husband reside in Atlanta with their two children. Michael Chriszt is vice president and regional engagement officer in the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta's Corporate Engagement Division. In this role, he serves as the Atlanta Fed’s lead public engagement officer focusing on smaller cities and towns in the Sixth District. Mike has served on several boards, most recently as Chair of the Georgia Council on Economic Education and on the executive committee of Kennesaw State University’s Coles College of Business. He is a member of the National Association of Business Economists and the Atlanta Economics Club, where he served as president from 2015 to 2017. A native of Cleveland, Ohio, Mike is married to Maxine and they have five children and three grandchildren. Colleen McEdwards is an online instructor with the University of Florida’s renowned distance-learning graduate program in communication and media studies (CJC Online). She designs and delivers online courses in video storytelling. After a 30-year career in international media at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and CNN International, Colleen transitioned to academia, helping new generations of communicators discover what’s next for digital media. She has taught at the Sam Nunn School of International affairs (Georgia Tech), Georgia State University, and Kennesaw State University. Prior to her transition to academia, Colleen spent almost 20 years as an anchor and correspondent for CNN International. Colleen earned a Ph.D. in Education while working at CNN International, partnering with CNN’s international affiliates throughout the process. She is a United States/Canadian citizen, a former competitive athlete and an avid sports fan. Sally Sears, an award-winning news reporter and author, is a founding director of the South Fork Conservancy. The Trust for Public Land named her its 2015 Trail Blazer for her leadership of the vision of linking communities with low-impact trails along the South Fork and other tributaries of Peachtree Creek. Her environmental and community work is an outgrowth of decades of news reporting in growing cities across the South. Special televised reports on solutions to north Georgia’s growth issues of water, land use, and traffic helped her find the broader community connections to create cooperation among partners. Sally covered politics and suburban growth for metro Atlanta television stations, including WAGA and WSB TV, since 1984. She served as the founding chair of the DeKalb County watershed oversight committee in 2009. Sally is a native of Montevallo, Alabama, and a magna cum laude graduate of Princeton University. She lives in Atlanta with her husband, Richard Belcher, and their son, Will. “We are excited to welcome Beth, Michael, Colleen, and Sally to the Birds Georgia Board of Directors,” says Paige Martin, outgoing board chair. “These individuals bring a wealth of talents and experiences to the Board that will help Birds Georgia fulfill its mission of building places where birds and people thrive.” Additional Birds Georgia board members include Paige Martin, Scott Porter, Esther Stokes, Joshua Gassman, Laurene Hamilton, Gus Kaufman, Mary Anne Lanier, Jennifer Johnson McEwen, Ellen Miller, Jon Philipsborn, Marlena Reed, James Renner, LaTresse Snead, Amy Beth Sparks, and Ayanna Williams. For more information on Birds Georgia visit https://www.birdsgeorgia.org/. About Birds Georgia: Birds Georgia is building places where birds and people thrive. We create bird-friendly communities through conservation, education, and community engagement. Founded in 1926 as the Atlanta Bird Club, the organization became a chapter of National Audubon in 1973, and continues as an independent chapter of National Audubon Society today. We look forward to celebrating the 100- year anniversary of our organization in 2026. Learn more at https://www.birdsgeorgia.org/. |

AuthorBirds Georgia is building places where birds and people thrive. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed